Uruguay Post #3

Nationalism is the support and promotion of interest of one’s nation, as well as loyalty and devotion to one’s nation. Zakaria defines nationalism as pride in one’s country, an assertion of identity. He states that as economic wealth increases, so does nationalism. He explains that many once poor countries which now command new wealth and power want to be seen and heard on the global stage.

The danger Zakaria sees in nationalism may not be so strongly categorized as such—he makes the point that overall the world is moving away from being “anti-American” and more “post-American”, in which there is no longer resentment and outward disdain for the former reigning world power but instead indifference as other countries catch up. Zakaria describes how these once third world countries which had no say in the decisions of the global north now have the power to carve their own identities and negotiate their own futures as they gain leverage in economic wealth and resources. Emerging countries will no longer bow to the will of America—countries such as Brazil have straight up denied American negotiations—and this is a new global stage that America, as well as the rest of the world, will need to learn to navigate.

Uruguay was initially a colony of Spain; the capital, Montevideo, was a military stronghold. Uruguay went through a revolution for independence in 1810, and the loose states between Argentina and Brazil were established as a state through a treaty in 1828. This treaty, mediated by Britain, came of the nation-state conflict of Argentina and Brazil both wanting the Uruguayan land. The treaty created a buffer between the two nations, and satisfied the Uruguayan’s people want for their own independence and identity. Internal war prevented stability for the first 25 years of independence, as the parties of the first two presidents, the Blancos and the Colorados, waged “The Great War”. The people of Uruguay were highly polarized in supporting either party, and the years of war wrecked the land, food supply, and the people’s wealth.

In the late 19th century, development began rapidly when large waves of immigrants from Europe moved into Uruguay. They set up businesses and introduced sheep, supplementing the damaged cattle industry and creating a new commodity for trade. The increasing output of goods such as wool, hides, and dried beef led the British to invest in Uruguayan public utilities and public transportation—which in turn encouraged even more immigration.

President Jose Batlle initiated incredibly progressive social reforms upon this period of prosperity in the early 20th century. A known Colorado hero, such examples of reforms included the elimination of the death penalty, allowing women the right to initiate divorce, the establishment of rights to children born out of wedlock, and the minimization of the power of the Roman Catholic Church. Additionally, he increased government regulation of the economy. With all of these reforms, Uruguay thrived throughout the early 19th century, until global economic demands shifted and Uruguay fell to economic instability and an austere dictatorship in the 1970s.

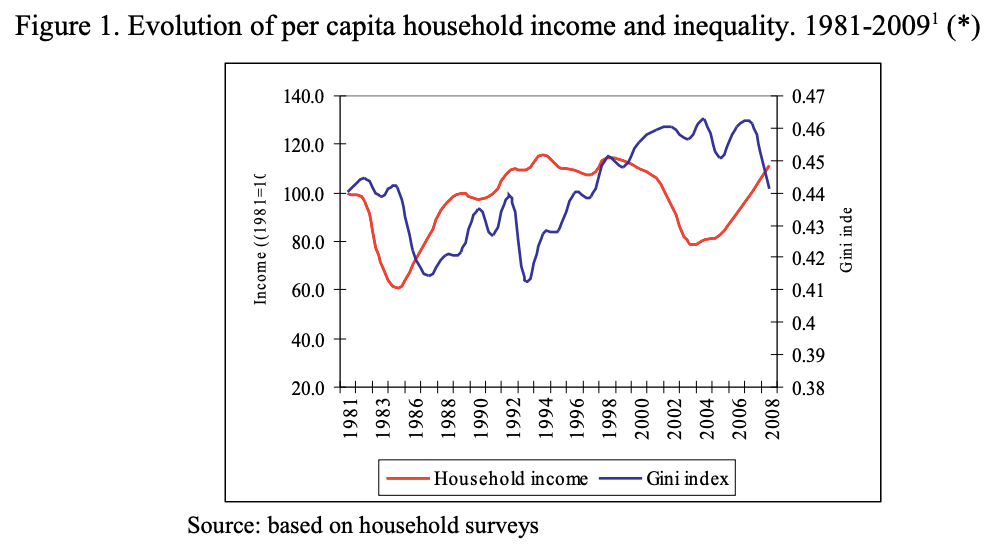

Uruguay returned to democracy in the mid 1980s, and has enjoyed a prosperous state since. Whereas many other South American countries experienced terrible inequality throughout the 80s and 90s, Uruguay remained relatively stable. The GINI Index sits at 39.50, and is one of the lowest of all Latin American countries, which likely fosters national pride. The Blancos and Colorados have alternated power, and the smaller factions are moderate and foster cooperation with a common vision to improve their country. This sense of democracy and love for one’s country permeates not only the government, but also the citizens of Uruguay. The culture built upon the work and cooperation of immigrants and each group’s contribution to society is appreciated by the Uruguayan people.

However, this peace does not come without the dark history of the elimination of the Native Americans who once inhabited the area. Uruguay is a prime example of globalization, and a prime example of what Steiger described in his introduction to globalization as the European conquest to “make the world in its own image”. As I described in my previous blog posts, the Uruguayan government was initially friendly with the native population, with established communications and trade agreements. This was violently disrupted when the Uruguayan president, upon the insistence the Europeans wishing to expand without opposition, initiated the genocide of the Charrúa. Following this, the European settlers simply continued the process they had already established—just as they transplanted the European philosophy, architecture, religion and culture from the European continent to the American landmass, they so too transformed the remaining natives from the genocide, integrating them into society as slaves, another lower class serving the European style. Eventually the remaining natives hid their own identity in order to survive in this new world, and their traditions, languages, and music died as their children conformed to this society in order to assert their futures.

One Uruguayan, Nicolas Guigou, stated, “When I was a child in school, I learned, ‘We are a very civilized country, very advanced, because we’re white and European and, thank God, we had no Indians’”.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/BNDKDQALC5HORF5XQPC5HRJ5PU.JPG)

Recently, however, groups have emerged claiming Charrúa identity and demanding recognition from the government as native peoples and as victims of genocide. CONACHA is the organization of 10 Charrúa collectives throughout Uruguay, which encourages people to claim their native heritage and fight for the governmental recognition of the genocide which occurred in the 1800s. The government is yet to recognize it as such.